It doesn’t get more epic or intense than filming one of the world’s apex predators. But what Steve Wall and his colleagues are doing spans deeper than adventure. They’re opening up a new way to think about shark behaviour… work that, in Steve’s view, could save lives on both sides of the equation: people and sharks.

So, what does this have to do with portable monitors? Read on… they’ve become essential in how the team captures, reviews, and makes sense of weeks of footage from some of the planet’s most remote waters.

Steve Wall: An Aussie film-maker in Iceland

Steve is a photographer, director and filmmaker specialising in remote locations and underwater cinematography. Based between Australia and Iceland, Wall works on productions and feature films, combining his passion for surfing and diving with conservation and storytelling. The ocean is his map for storytelling.

Born and raised in coastal Australia, Wall has always had a connection with the ocean through surfing, swimming and content creation. In the past few years he moved to Iceland with his partner after they connected on a road trip adventure across Australia.

"She took a leap of faith to fly to Australia. I was just about to drive Sydney to Perth, filming underwater ocean stuff. She joined me on that trip. We spent five weeks living in the roof tent of my Land Cruiser," Wall said.

Upon moving to Iceland, Wall discovered a cultural contrast between Australia’s ocean-centric lifestyle and Iceland’s view of the sea as hostile territory. This observation drove him to pursue ocean filmmaking and storytelling in Iceland in order to help positively impact people’s understanding of the ocean to achieve a better conservation outcome.

"People can't care if they don't connect with something. So that’s the first step if you want to protect the natural world.”

From Iceland to Australia's Shark Frontier

Fast-forward to 2025, Steve and his crew are trailing a group of passionate researchers on an ambitious project to observe shark behaviour in some of the most remote, untouched, and out-of-reach areas of Australia’s wild Western coast.

Wall and his team are exploring an ancient theory that could help us coexist with these apex predators.

"Few things strike primal fear into our hearts like the shark," Wall explains. "We're following a team of intrepid ocean experts and scientists on a very unique process. I’d say the stakes are high, success could be a huge win for not only our own safety in the water, but for the entire marine ecosystem.“

The Crisis: Australia's Shark Problem

As a lifelong surfer and diver, Wall has always been an observer of Australia’s escalating shark encounters.

"In the last decade, Australia has seen the biggest increase in recorded shark interactions on the planet. There are so many mysteries around exactly what is going on, yet such enormous challenges in even attempting to reach a definitive answer."

The story explores the true impact coastal communities have felt: "Places like the Eyre Peninsula in South Australia and Southern WA and the Northern Rivers region of NSW. As a surfer, it comes with the territory when you spend time in the water in these places."

“These stories of lived experience set the scene for the project. Can we reconcile some of the harrowing experiences of veteran watermen and women with a rigorous scientific process, whilst looking past our many inherent biases in such a heavy and emotive topic.”

Local Wisdom Tested By Modern Science

A spark for this project came when Steve met Shanan Worrell, a surfer, adventurer, and former abalone diver from Western Australia.

"Their community used the concept of biomimetic eyespots as a shark deterrent. They would silicon fake eyeballs on the back of their wetsuit, in a response to the knowledge that sharks would always change behaviour and become more cautious when you made eye contact with them underwater. Not exactly the kind of insight you get about sharks as a surfer in Sydney, but what decades in the water in southern Australia can give you” Wall said.

Despite widespread adoption from professional divers, spearfishermen and scientists, the idea has remained little understood outside of these communities, the domain of anecdotal experience in far-flung corners of the ocean.

"These are guys who are in the most high risk environment, perhaps on the planet when it comes to sharks, who probably spend the most time of almost anyone on the planet interacting with these animals. And yet this knowledge has never really gone beyond this hardcore community.

“As I came to understand more about the idea, I learnt that this started long before a group of Australian divers.

“Indigenous communities around the world had used the concept for protection, hundreds of species in nature had evolved to use eyespots for defence and more recently our human study of biomimetic design was delivering unimaginable and mind-boggling findings to some of our most complex design and engineering challenges. There was clearly a lot to this, and I thought a film could be a great way to explore the idea.”

Testing the Theory with Hours of Film

Putting ideas and insight to the test, it was clear that an experiment needed to take place to try and understand if the eyespots actually alter shark behaviour, and if so how?

"We started looking at where you need to go to run research like this. You need to find a site far from civilization, both out of respect for the local community and to try and create the most natural conditions possible. It’s very difficult to find a place accessible enough to run a multi-week expedition with normal resources, yet be far from the impact of big cities and cage diving tourism.

Not to mention, how do you create an artificial experiment that is supposed to truly replicate the real world scenario of a shark’s investigation process? To suggest that we can fool a shark into thinking it’s eying off a prey species, rather than a plastic bucket - i’d say that is ignoring everything we know about the intelligence of these apex predators. Something that may work with smaller species that don’t threaten us, may be completely ineffective with white sharks and other bigger species”

The Logistics and Workflow Challenge

The remote nature of the research creates unique technical demands.

"When we go on these expeditions, it's weeks away from civilization. It's unique for me in that it's in parallel both a scientific expedition and a film production at the same time."

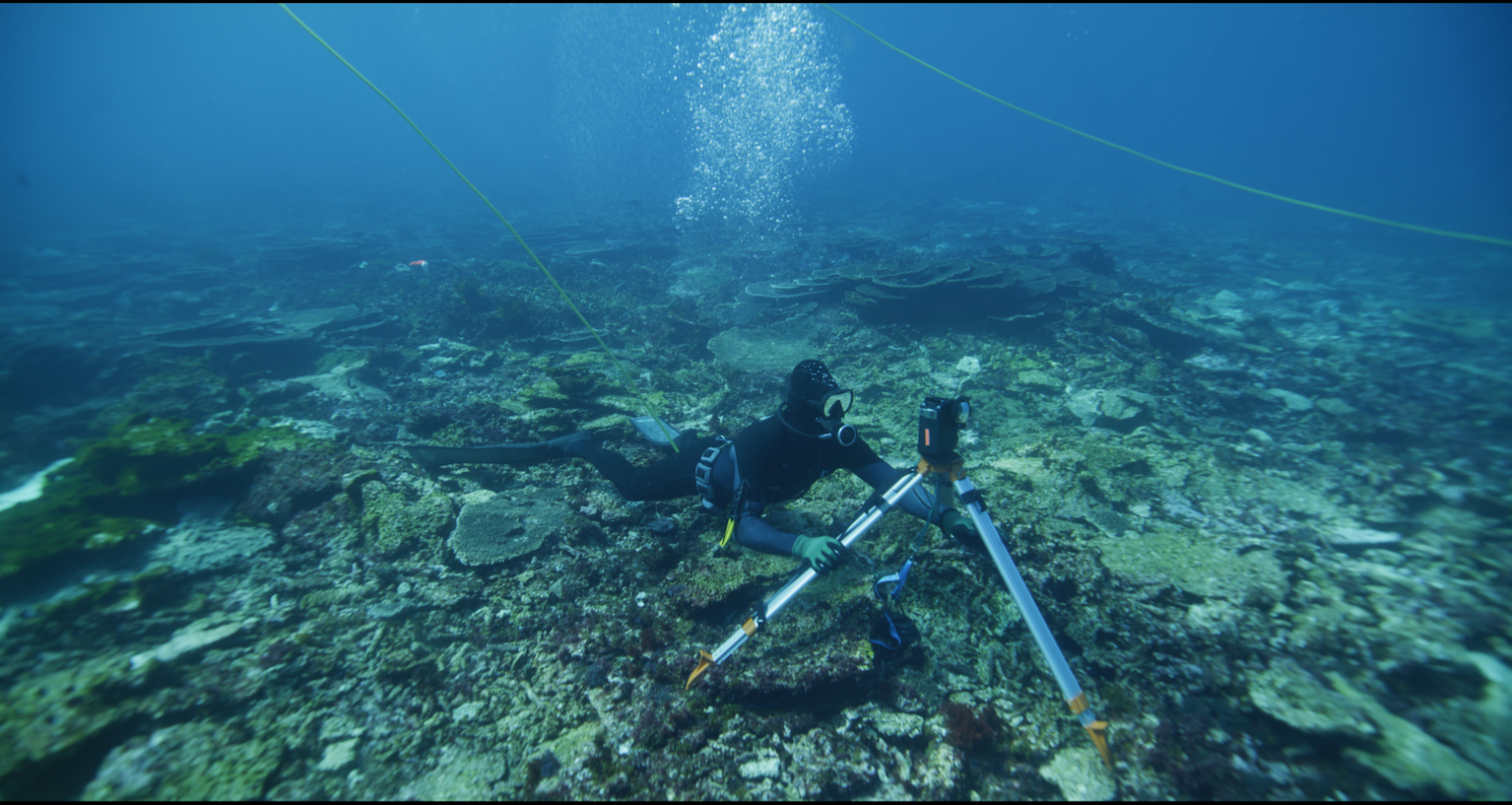

Equipment includes "maybe 10 to 20 Pelican cases full of underwater housings, gimbals, drones, the usual camera equipment, and we also have this specialised data collection set up, which is four long deployment underwater camera systems I developed that can run for up to 16 hours each."

The Workflow: “The Displays earned their place”

The team's daily workflow is intensive for Steve and his team. When you’re in the wilderness, you carry and work with the essential tools, and they need to work every time. The process involves heavy manual reviews of hours of content captured underwater. The reviews happen on a set of espresso Pro 17-inch portable monitors.

"Every day we'll go out to the site, set things up, drop these cameras down into the water. They stay down there all day until we pack up at night. We'll come back to the island or land camp, and then our data wrangling process begins by pulling terabytes of high quality underwater recordings to review."

Power limitations in remote locations also create specific requirements.

"I knew that going on these trips, it’s not like working on a desktop computer or large external displays that require 240 Volt power. Often our base is set up with an EcoFlow power supply or a generator."

Wall discovered espresso Displays portable monitors at the perfect time:

"I actually didn't know such a thing existed until I came across espresso one day, and this was actually before the needs of this project were clear. So when I was trying to figure out how on earth we’re going to pull this off, I was amazed that there was a solution already out there that was a perfect fit."

Portability was crucial:

"We're travelling in small boats, we're travelling in small planes. This project has the demands of a huge budget feature film, but with the resources of a group of likeminded mates that wanted to unravel some mystery and tell a good story - so we’ve gotta be agile and find solutions. Sometimes I need to move gear either across Australia or across the world, so a second display that can go in a laptop sleeve with me that can give me so much functionality. It's such a win."

The Nightly Content Review Marathon

The team's post-production workflow reveals the setup's importance.

"Our post production workflow is basically just a nightly turnover of this huge quantity of data, where we'll then synchronise the four camera angles and create a master project in DaVinci Resolve."

"It's a full time job just to turn over the cameras, sync and manage the data. Without a clean turnover each night, we can’t go out again the next day. So a Macbook Pro and two espresso Displays became our workstation.

That was the first thing we would do coming off the water every day. We'd just open up the cameras, pull cards, get those backing up, get those turned over, and hopefully by midnight we'd be turned over and ready to go again for a early AM start the next day."

Unexpected Discoveries

The research has challenged assumptions about shark behavior.

"I think it's fascinating to explore our human bias around sharks. Like most things in the world, the reality is a lot more nuanced and complex than we’re led to believe.

“Sharks are a lot more cautious than you might think and their prey can very much bite back. We often see sharks painted as the image of our worst nightmare, which is certainly the reality for some - tragically. Yet at the same time, sharks are a keystone species of the marine ecosystem, so their numbers and health are a non-negotiable prerequisite of a healthy ocean - without them, everything further down the chain collapses and of course, that includes us in the end”

The Conservation Stakes

Wall and the team behind this experiment are motivated by more than just science.

"If this keeps one person even a little bit safer in the water, then it will all be worth it. If it makes people look a little deeper into the mysteries and wonder of the sea, then it’s all worth it. This is a space shared by marine scientists and those who enjoy the water recreationally or professionally - we’re all just experiencing and learning in our own ways”

The broader implications of this work are serious and the ecological stakes are high.

"The reality is if we don't coexist with any given species, historically it does not end well for that animal. If these shark attacks continue, pressure will force governments to act in the interest of public safety, tourism and perception - leaving them with little option but to cull.

"We need apex predators. We need sharks. But we also need to protect our personal safety. Both things can be true at once, but a better understanding is the only way forward.

Impact Beyond the Lab

"You could easily spend 5 or 10 years diving into this project, with millions of dollars of funding" Wall reflects. "So the fact that a group of underwater filmmakers and divers and scientists have gotten together to try and do this with their own resources and motivation is something special.

"Any solution that positively contributes to sharks and humans coexisting better is only a great thing for the healthy future of the ocean and the planet," Wall adds.

Looking Ahead

Steve and the team have completed two rounds of preliminary research on expeditions to two different parts of Western Australia, with further testing in the not too distant future.

"One of our big trips is going to be to spend a month out in the desert coast, far from civilisation, that will be like the craziest logistical operation of the whole thing. Day after day in the water, returning to a remote camp, basically on a beach with tents and solar panels trying to keep sand out of everything."

Even in these extreme conditions, the portable monitor setup remains essential: "In between that it will be shooting and I imagine we'll be using the espresso just on the tailgate of my truck."

With his feature documentary planned for premiere in mid-2026, Steve and the team can’t wait to share what they found with the world.

Where to learn more:

You can follow Steve via his website and his incredible content on social media (@whereswalle).

We’re incredibly inspired by Steve’s story and look forward to following his adventures in Iceland and Australia. We’ll work to update this story with a follow up in future. Thank you, Steve, for sharing your story with us.

Steve’s Expedition Production Kit Breakdown

Every item earns its place. Weeks from civilization, travelling in small boats and planes, Steve’s setup has to survive salt, sand, and zero power outlets.

- 10–20 Pelican cases for carrying all gear into remote field sites.

- Underwater housings for protecting cameras for long ocean deployments.

- Gimbals for stabilising shots on moving boats and in rough conditions.

- Drones for aerial coverage, safety and site scouting.

- Long-deployment underwater camera systems for up to 16 hours runtime on tripods, capturing shark and fish trajectories.

- MacBook Pro for the core of the field workstation.

- DaVinci Resolve for heavy and consistent video editing.

- Dual espresso Display Pro 17 monitors. Portable, USB-C powered, and essential for reviewing and syncing terabytes of footage.

- RAID SSD storage units for fast, rugged storage for nightly backups.

- EcoFlow power supply or generator for keeping kit running when mains power isn’t available.

- Tents and solar panels (for December’s month-long camp) — turning a beach into both a science lab and film set.

.png)

.png)